Written by: Carolina Parreiras & Renata Mourão Macedo

Brazil is a country marked by intense digital and educational inequalities. In the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a federal government that stands as an enemy to education, such inequalities are accentuated. In this sense, our proposal is, from the sum of our research experiences on technology and education, to draw lines of analysis that help to understand how the process of migration of basic education [1] and higher education to digital platforms unfolded. The inspiration for this essay comes from our previous research and our involvement with situations - both at the university and in our fields of research, and personal lives - that show how urgent the debate regarding distance education/remote learning is, particularly considering questions of inequality and social markers of difference. We start from a perspective that does not demonize or believe in catastrophic visions of technology, but that proposes to think about its many uses and the many contexts in which it is inserted in order to better understand the challenges that these uses contain.

As a brief overview of the situation in Brazil, even before the pandemic there were substantial [2] cuts to education, with its budget reduced by 16% only in the first year (2019) of the Jair Bolsonaro’s government, in addition to successive changes in the minister of education (the last of which happened amid the pandemic). It is worth remembering that a considerable part of the educational system in the country is public and depends on government funding.

Since March 2020, with the establishment of social isolation measures, a large part of the educational system - both basic education and higher education - has adopted measures to continue teaching through distance education or remote learning. It is important to point out that there is a debate around the terms themselves - e-learning/distance education, and remote learning. Although distance education is regulated by the Brazilian Education Guidelines and Bases Law (LDB), it requires planning, forms of management, and that part of the workload be fulfilled in person. Remote education, on the other hand, represents the alternative that was precipitated by the pandemic, with the rapid replacement of classes, schools, universities, and classrooms by the use of digital platforms.

One of the questions that arises is that, in this assembly of remote education, many social and digital inequalities are not taken into account, as, so far, the proposal has been to migrate activities to digital environments without addressing a basic problem: not everyone has access to, and masters the use of, technological devices and network connections. If it was previously a constant challenge to reduce dropout rates and guarantee student permanence in schools and universities, we now have an even more serious situation, and one that is difficult to solve immediately.

In this article, we use the idea of digital inequalities as the center of our argument, which refers to non-egalitarian processes of access, digital literacy, and the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), making it essential to consider social markers of differences such as social class, gender, race and age, as well as other contexts and contingencies. Other possible designations to this issue would be that of digital inclusion [3] or reducing the digital divide[4]. Although there are subtleties in these definitions, in general, both point to unequal processes of access to technology and the internet. We work with the hypothesis that digital inequalities mirror, “replicate” (Oyedeme, 2012), and reproduce wider social inequalities. It becomes necessary, then, to reflect on how this affects the proposals and experiences of remote education carried out in Brazil during the pandemic, given the impossibility of the full reopening of schools and universities in the short term.

Although in the last 15 years there have been considerable improvements in infrastructure and access to technology, we can say that Brazil still has high rates of digital inequality [5]. For example, in the National Survey of Brazilian households (PNAD) in 2018 [6], 41.7% [7] of Brazilian households had a microcomputer, and only 12.5% had access to a tablet, with considerable differences between the regions of the country. In the case of Internet access, it was used in 79.1% of households, with the majority of these accesses being made by cell phone (99.2% of total accesses used cell phones, and in 45.5% of households cellphone connection was the only way to have access to the Internet). Mobile data networks (3G and 4G) were identified as the main sources of access (80.2%), surpassing residential broadband networks. Among the answers by those who declared they did not use the Internet, two reasons were given that call our attention: the high cost of the service (25.4%), and the lack of knowledge as to how to use technologies (24.3%).

Regarding the use of the internet, 74.7% of the people interviewed declared to have used the internet at some point in the 3 months prior to the survey. Something important to note is that there are striking regional differences in this number, and the influence of markers such as age, as well as a disparity between accesses via cell phones and other devices. Among those who declared themselves to be students, only 59.9% said they used a computer (again the cell phone is the most used medium). Among the students, those who said they did not have access to the Internet pointed out that the main reason for this reality is the cost of access to the service (26.4%), followed by the high cost of the access equipment (18.8%), and not knowing how to use technology (15.9%). Finally, it is curious to note that among students, they mostly do not mention the use of technology and the Internet for their studies or classes.

The data from another Brazilian survey [8], entitled TIC Domicílios (ICT Households), helps to give an overview of the use of technologies in the country. In the 2018 survey, 93% of households reported having a cell phone, 27% a laptop, 19% a desktop computer, and only 14% had a tablet. Regarding the presence of internet in homes, 67% had some type of access, 62% by broadband, 39% by cable or optical fiber, and 27% by 3G or 4G mobile connection. Regarding the reasons pointed out for the lack of connection, the financial factor (“because the residents think it is very expensive”) - 61% - and the inability to use the internet (“because the residents do not know how to use the internet”) stand out, having been declared by 45% of the survey participants.

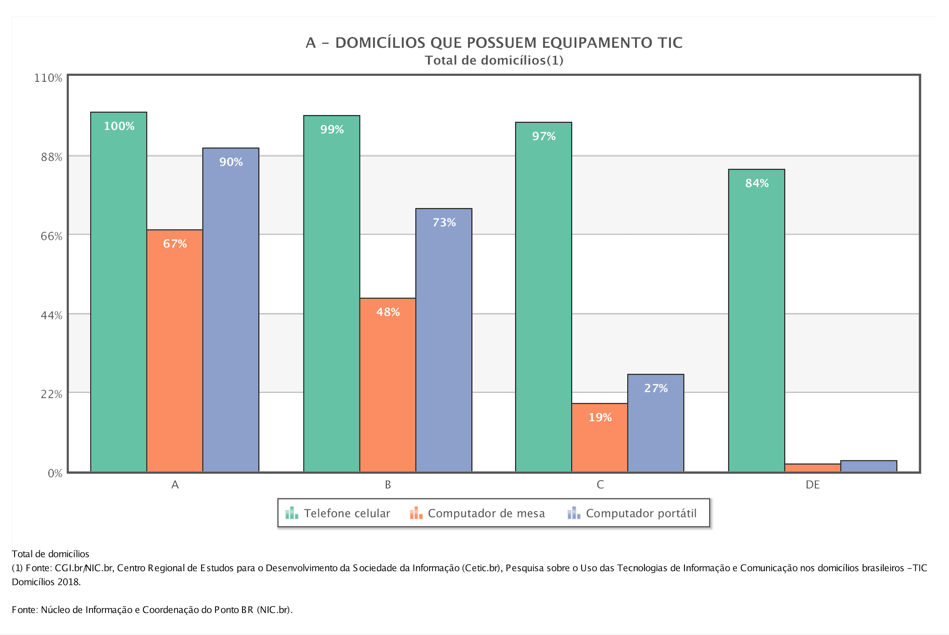

What these data show is that access to technology and internet connection are extremely uneven in Brazil. The considerable use of cell phones and mobile connections is noteworthy, both are less costly as compared to computers and broadband/cable/optical fiber connections. If we compare the data on access to technological devices with the variable family income, the discrepancies become very relevant. The graphs below help to visualize the Brazilian digital inequalities when we think about social class and income:

Graph 1: Households with access to Internet in Brazil. Source: TIC Domicilios, 2018.

Graph 2: Households with access to ICTs. Source: TIC Domicilios, 2018.

Graph 3: Households with ICTs by income group. Source: TIC Domicilios, 2018.

Graph 4: Types of internet access by social class. Source: TIC Domicilios, 2018.

Graph 5: Households with internet access by income group. Source: TIC Domicilios, 2018.

In May 2020, the first results of the report TIC Domicilios 2019 were published, and some data from the published report are noteworthy. Among them, we find that 20 million Brazilian households do not have internet (28% of the total amount). When we intersect this data with social class [9], inequalities appear again: while in classes A and B the presence of the internet is close to 100%, in classes D and E, it drops to 50%. There was also a decrease in home use of computers. If we cross this last data with social class, the disparities are striking: in classes A and B, computer is a common item (95% and 85%, respectively), while in classes D and E, its presence in the household drops to 14%.

Regarding data on users, 1 in 4 Brazilians do not use the internet (47 million non-users) and, among those who have access, the cell phone is the most used device (and 58% only access to the Internet through their cell phone). It is noteworthy that there has been a considerable increase in Internet access through television, an item that is more easily found in homes, and which can be purchased at a lower cost. In relation to the activities carried out on these devices, in the survey there is an item dedicated to education and work, which provides the option “took courses at distance education” of which only 12% of people declared to carry out. Finally, in June 2020, the ICT Education report was published, which aims to understand the access, use, and appropriation of ICTs in private and public schools. Once again, the inequalities found are clear. In this survey, only 14% of public schools declared to use any platform or digital learning environment (compared to 64% in private schools). Another relevant fact is that 58% of the students declared to use the cell phone for school activities, and 18% of them only have mobile access. Regarding teachers, only 33% said that they had had some kind of training in using the computer and the Internet for school activities.

Despite such inequalities, remote learning has imposed itself on Brazilian public and private institutions, in basic and higher education, since March 2020, when COVID-19 reached Brazil. As stated earlier, our goal is to think about the use of digital technologies and techniques, understanding, above all, processes of inequality, without establishing hasty and hermetic value judgments. Therefore, we emphasize that the macroscopic data available points to dynamics of exclusion, and the need not to envision the intersection of education and digital technologies as a tableau, but as a relationship marked by differences, subtleties, and inequalities that reflect broader exclusionary and uneven dynamics found in Brazil. Pointing to these mechanisms of inequality is a first step towards carrying out practical and more inclusive actions. In this context of crisis, technologies can both solve and expand communication and connection possibilities, but they can also be an instrument of commodification and precariousness in Brazilian education, reinforcing logics of exclusion that were already in process. It seems unrealistic, due to the serious widening inequalities in Brazil, to require that all students be able to connect, both in terms of technological aspects (equipment, connections) and regarding their knowledge of how to use platforms for online classes. It is worth remembering that virtual classes represent a novelty for large parts of students and teachers and involves knowing how to deal with different digital languages - texts, videos, images.

Regarding Brazilian higher education, it should be noted that, since the 2000s, there has been a great expansion of these institutions, which now allow for the inclusion of an important portion of Brazilians who never would have imagined reaching this stage of their education (Sampaio et al., 2019; Macedo, 2019). In 1995, there were 1.7 million enrollments at universities, a number that reached the mark of 8.4 million in 2018. If this process represented an important democratization [10] of higher education in the country, especially for black and low-income students, there was a parallel unprecedented process of commodification and privatization of education, in which the private sector became responsible for a large part of enrollments, accounting for 75% of enrolment in 2018 (INEP, 2018 [11]). In this process, within the continuous effort to reduce costs on the part of large educational companies, distance education emerged as a promising and profitable bet, representing 45.7% of the enrollments for those entering the private network in 2018, almost half. Low-quality, textbook-based content, pre-recorded lessons transmitted to thousands of students, and precarious teaching are known consequences of the rise of large educational companies, making Brazil “a unique case in the world” with regard to the neoliberalization of education (Laval, 2019, p. 13). In the current context of the pandemic, many of these private institutions took advantage of this structure already set up for distance education to dismiss [12] hundreds of teachers who previously occupied their classrooms in person. In some cases, it was also a progressive bet to replace teachers and tutors with artificial intelligence software [13].

Public higher education, on the other hand, despite representing only 25% of Brazil's enrollments in 2018, maintained its commitment to democratization, in addition to remaining mostly in person. Faced with the interruption of classes due to the pandemic, different actions are being taken. While some large public universities - such as the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) - have postponed the semester that would take place in early 2020 so as not exclude thousands of students who do not have a computer or internet at home [14], other institutions are trying to adapt to digital possibilities to continue providing courses. The University of São Paulo (USP), for example, chose to continue the academic semester online, but, for that, it sent two thousand Internet kits to low-income students who did not have access to these services, a number that certainly did not solve the digital inequalities of its approximately ninety thousand students [15].

While the death toll from COVID-19 continues to rise in Brazil - the country ends the month of June with more than 50,000 deaths - the far-right federal government led by Jair Bolsonaro disdains the population, attacking the Brazilian people on different fronts. In education, it has been no different. The Ministry of Education, in the midst of troubled management that resulted in the recent dismissal of the minister - refused to postpone the largest Brazilian admissions exam to universities - called ENEM – stating, in early May, that the educational system “was not made to correct injustices”. On the contrary, the then minister created a media campaign that stated that, even in the face of a pandemic, “life cannot stop”, suggesting that all students study on the internet: “it is necessary to fight and reinvent yourself”, stated the campaign. After great popular pressure via social networks, the date of the exam will be modified.

In basic education, the challenges are even worse. Surveys carried out so far point to an increase in inequality between students from the private system (which mainly serve students from upper and middle classes in Brazil) and students from the public educational system. What we see is that, among the private schools for the upper and middle classes, of which a majority of students were already connected and used to surfing digital teaching platforms, the study routine remains firm, despite the anxieties experienced by mothers, fathers, and students pressured by the uncertainties regarding the current situation in the country. Once again, we use data from the 2019 TIC Educação survey: 64% of Brazilian urban private schools already had some kind of platform for online education, a number that is reduced to 14% in the urban public network[16].

At the opposite pole, several schools try to address pre-existing inequalities, trying to find out how many of their students access the Internet or not in a stable way, under what conditions, and through which digital platforms. As we know from our different ethnographic surveys in urban peripheries, even regularly accessing an email account is an important marker of social class in Brazil. Such access becomes even more difficult without adequate equipment. In the public network of São Paulo - the most populous state in the country - the government has created online content to be transmitted through an application, in addition to alternative transmission through a television channel. However, recent data show that, of the 129,000 students enrolled, on average, only 27% of students have been able to track the activities on the app [17]. The immediate answer seems to be that a large proportion of students from lower social classes are once again being excluded from this educational process.

In the case of Parreiras, there are constant reports from her field [18] on the difficulties posed by the migration of studies to digital platforms among favela residents in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Many of the mothers in her research complaint about their lack of knowledge regarding the use of teaching platforms, as well as the difficulty and cost of accessing the Internet, which is done mostly through mobile data networks (always insufficient for school requirements). Adolescents involved in her research, on the other hand, are divided between fear about the future (especially in relation to the National High School Exam, which guarantees entry to universities), and complaints about the difficulty of adapting to classes on digital platforms, and the challenges of obtaining adequate access to these classes. As one of her interlocutors stated:

“my technical course is going down the drain, because I don't have the necessary tools to continue with this 'distance education' that doesn't think about all students, that not all students have the financial means to attend online class… ”

Macedo has also accompanied several families who are unable to access remote education, either in her neighborhood in the western part of the city of São Paulo, or through colleagues of her eight-year-old son, who studies at a public school. This is the case of Juliana, one of the other mothers at this school who is a cleaning assistant in a private cleaning company, who accesses the Internet exclusively through a smartphone with prepaid Internet at home. So that her son can follow some online meetings held by the teachers, Juliana and the boy, both wearing masks, have to cross the entire neighborhood to go to an acquaintance’s house who has Wi-Fi access and has accepted to receive them. On the days that this neighbor leaves for work and cannot open the house for her, Juliana's son is forced to miss online meetings with the teacher.

In this context, reflecting on digital inequalities and education, it is essential that in Brazil, unlike other countries, the government not believe that remote learning solutions will be unequivocal. This process cannot be carried out without taking into account the diverse contexts in which students and teachers are located, for education is under the risk of further intensifying the processes of social exclusion. If we believe that one of the goals of education is to promote and cherish diversity, it will be up to Brazilian society to find creative and diverse solutions to keep education active and capable of building new paths during these hard times of a pandemic and post-pandemic.

Author Bios

Carolina Parreiras is an anthropologist; postdoctoral researcher at Department of Anthropology (University of São Paulo – Brazil), Adjunct Professor at the Graduate Program in Social Anthropology (State University of Campinas – Unicamp) and member of NUMAS – Center for Studies of Social Markers of Difference. The research project that led to this article was funded by São Paulo Research Foundation (Project Fapesp n. 2015/26671-4).

Renata Mourão Macedo is an anthropologist, postdoctoral researcher at Department of Education (University of São Paulo – Brazil) and member of NUMAS – Center for Studies of Social Markers of Difference. The research project that led to this article was funded by São Paulo Research Foundation (Project Fapesp N. 2019/25903-0).

References:

Bradbook, G and Fisher, J. (2004). Digital Equality: Reviewing Digital Inclusion Activity and Mapping the Way Forwards. London: CitizensOnline

Helsper, E. (2008). Digital inclusion: an analysis of social disadvantage and the information society. Department for Communities and Local Government, London, UK

Laval, C. (2019) A escola não é uma empresa: o neoliberalismo em ataque ao ensino público. São Paulo: Boitempo.

Macedo, R. M. (2019). “Políticas educacionais e a questão do acesso ao ensino superior: notas sobre a deseducação”. Cadernos de Campo, v.28, n.2, Available from: http://www.revistas.usp.br/cadernosdecampo/article/view/163922

Oyedeme, T. D. (2012) Digital inequalities and implications for social inequalities: A study of Internet penetration amongst university students in South Africa. In: Telematics and Informatics. Vol. 29, n.3, ago. Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0736585311000888

Parreiras, C. and Macedo, R. M. “Desigualdades digitais e educação: breves inquietações pandêmicas”. Boletim Anpocs N.36. Available from: https://www.anpocs.com/index.php/ciencias-sociais/destaques/2350-boletim-n-36-cientistas-sociais-e-o-coronavirus

Sampaio, H. et al. (2019) “Expanding Access to Higher Education and its (Limited) Consequences for Social Inclusion: The Brazilian Experience”. Social Inclusion , V. 7, I.1, pp.7- 17.

Spyer, J. (2017). Social Media in Emergent Brazil. London, UCL Press.

Telles, E. and Paixao, M. (2013) "Affirmative action in Brazil." LASA forum. Vol. 44. No. 2.

Van Dijk, J. (2006). “Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings”. Poetics, vol. 34, n. 4-5, p. 221-235.

Footnotes

[1] In Brazil, the stages of formal education are divided into "basic education" (corresponding to Primary and Secondary Education in UK) and "higher education". Basic education is divided into Elementary school (Ensino Fundamental) and High School (Ensino Médio). In this article, we use the Brazilian classification.

[2] https://www.terra.com.br/economia/bolsonaro-corta-investimentos-em-educacao-saude-e-seguranca,a0c81ff72f5ab50614d67ac1bd1b057a392c245i.html

[3] The term digital inclusion points to a reversal in dynamics of exclusion in relation to access and use of technologies, denoted by the term inclusion. Helsper (2008), in reviewing the bibliography on the topic, relies on Bradbrook and Fisher (2005) to propose that in determining the grounds for digital inclusion we have to consider “connectivity (access), capability (skill), content, confidence (self -efficacy) and continuity ”and that the Internet and communication and information technologies are thought of as part of the “infrastructure of everyday life”.

[4] According to Van Dijk (2005), digital divide represents “the gap between those who have and do not have access to computers and the Internet” (p. 221).

[5] For research that analyzed the recent process of democratization of the internet and social networks in Brazil, see Juliano Spyer (2017).

[6] The survey was conducted with a focus on residential access to the Internet and television, and access to mobile Internet and cell phones (with individuals over 10 years old).

[7] The report notes that, since 2016 when the first survey was conducted, there has been a decrease in the number of homes with computers. The explanation for this is the replacement of the computer and tablets with cell phones. This would not be a problem a priori, but it is one of the factors that makes it difficult to use certain digital platforms or environments for remote learning.

[8] The research is carried out by Cetic.br, linked to the Internet Steering Committee in Brazil (CGI.br). Unlike PNAD, its focus is exclusively on issues related to information and communication technologies. http://data.cetic.br/cetic/explore?idPesquisa=TIC_DOM

[9] Among the categories used to measure social stratification in Brazil, there are the so-called “socioeconomic classes”, which can be defined based on criteria such as household income, per capita income or consumption potential. In such classifications it was agreed to name the strata by letters, starting at the top of the social pyramid with the letter A - the richest -, and ending in the letter E, the poorest. These classifications are used by the market, the government and research institutes

[10] It is worth remembering that, since the law passed in 2012, Brazil has a national affirmative action quota policy system, allocating 50% of vacancies at federal public universities to students self-classified as black and low-income (Telles and Paixão, 2013).

[11]http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/censo_superior/documentos/2019/apresentacao_censo_superior2018.pdf

[12] This is the case, for example, of the network of colleges called Uninove, which in June 2020 laid off 300 teachers. https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2020-06-24/em-meio-a-pandemia-fomos-tratados-como-numeros-diz-professor-demitido-da-uninove.html

[13] https://www.uol.com.br/tilt/noticias/redacao/2020/06/24/laureate-usa-robos-no-lugar-de-professores-sem-que-alunos-saibam.htm

[14] https://ufrj.br/noticia/2020/03/23/coronavirus-ufrj-suspende-aulas-por-periodo-indeterminado . According to the dean of UFRJ, Denise Carvalho, about 10 to 15 thousand students at UFRJ will need help to access the Internet in their homes. Available at: https://ufrj.br/noticia/2020/05/27/ideia-e-conseguir-acesso-todos-afirma-reitora-sobre-aulas-remotas

[15] https://jornal.usp.br/institucional/usp-distribui-mais-de-2-mil-kits-internet-para-estudantes-com-necessidades-socioeconomicas/

[16] ps://cetic.br/pt/noticia/escolas-estao-mais-presentes-nas-redes-sociais-mas-plataformas-de-aprendizagem-a-distancia-sao-pouco-adotadas/

[17] http://www.apeoesp.org.br/noticias/noticias-2020/levantamento-da-apeoesp-mostra-que-ensino-a-distancia-tem-participacao-media-de-27-3-dos-alunos/

[18] All ethical precepts, supported by the deliberations of the Brazilian Association of Anthropology and São Paulo Research Foundation’s financing rules, were followed. The conversations with interlocutors took place through the WhatsApp. The use of part of these conversations was allowed by explaining the purpose of the work (informed consent) and the mentioned interlocutor was anonymized.